I often wonder if corrections to content in one issue of a magazine or newspaper that get published in a later issue mean anything to anyone other than the individual victim of the mistake (if there happens to be one). Experience has taught me that, once in print, such mistakes are like the evil in the men of ancient Rome: The initial wrong lives long after the belated correction.

In my salad days I read the 1955 date of Jane Byrd McCall Whitehead’s death off the plaque on her family gravestone with my own eyes, but a typo in my 1984 article about the Byrdcliffe Arts and Crafts Colony written for The Magazine Antiques transformed 1955 to 1935. This was hardly a minor error because I wrote that the Widow Whitehead lived on for years after her husband died as a virtual recluse among the leftovers from the ambitious Arts and Crafts experiment they started. Since Ralph Whitehead died in 1929, the incorrect 1935 date nullifies my point. The error persisted when the article was adapted for an exhibition catalogue. Subsequent corrections were published, but they of course do not appear when scholars dredge up the original published text. To this day I get questions about the disparity between my account written some 25 years ago and the more recent exhibition catalogue for the 2004 exhibition based on my research.

The Magazine Antiques was still the oracle of decorative arts research back then, but they seldom published corrections and I don’t believe they ever had a Letters to the Editor section where readers could question what they read. Now that the magazine is wizened to a ghost of the grand old lady she once was, she seems desperate for anything written by anyone no matter what his or her credentials. Accuracy is no longer an issue, and authors can get away with writing history to suit themselves.

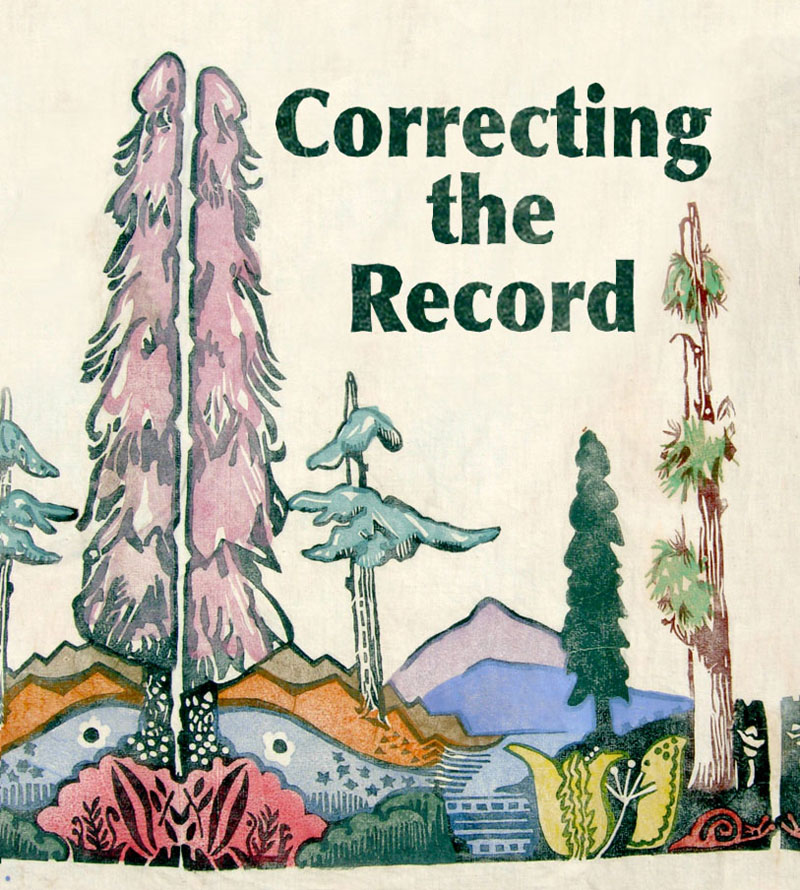

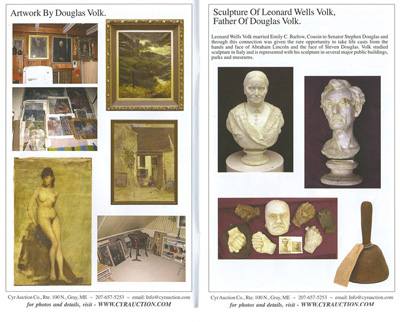

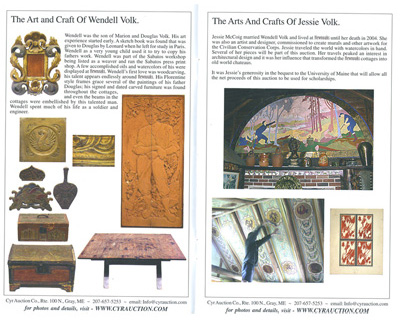

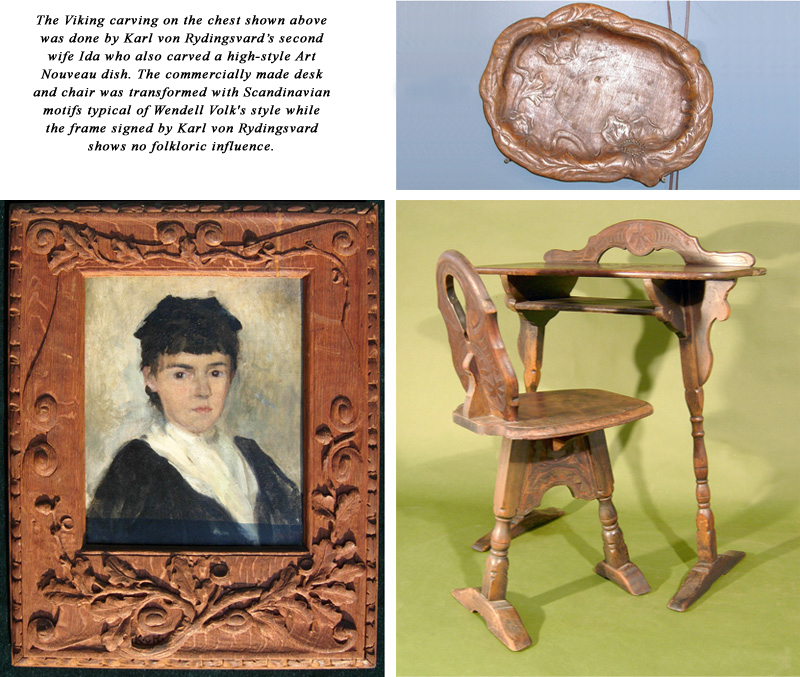

A case in point is a 2008 article about Hewnoaks. There was an incredible amount of material sold at the 2006 estate auction of the lakeside home of the multitalented Volk family. Leonard Volk (1828–1895) was a sculptor most famous for making a plaster cast of Abraham Lincoln’s face in 1860. The cast was one of only two made while Lincoln was alive, and Volk used it as the basis for a full-length statue. His son Douglas (1856–1935) was a painter who married Marion Larrabee. Their artist son Wendell (1884–1953) married Jessie McCoig, also an artist, who bequeathed the Volk estate to the University of Maine after donating a fraction of the family records to the Smithsonian’s Archives of American Art.

Jessie (and the university) probably didn’t realize that her family’s artistic heritage would rest largely on their activities associated with the Arts and Crafts movement, so the textiles, woodcarving, paintings, and metalwork made at Hewnoaks were treated with little respect and ended up as auction lots along with huge cartons of documents and family photographs. Even so, a scholar wishing to give the Volks their due could have taken the time to contact buyers of those lots in order to write a more complete overview.

Instead, the author evidently chose to rely on the Archive, the few things that the Maine Historical Society was able to acquire from the auction and, most tellingly, the objects she and her husband bought for inventory. The couple is part of a cadre of dealer duos who believe their considerable knowledge of American antiques (particularly ceramics and glass) entitles them to a stranglehold on the market. Their vituperation in the face of bidding competition would be comic if it didn’t result in a venal manipulation of history.

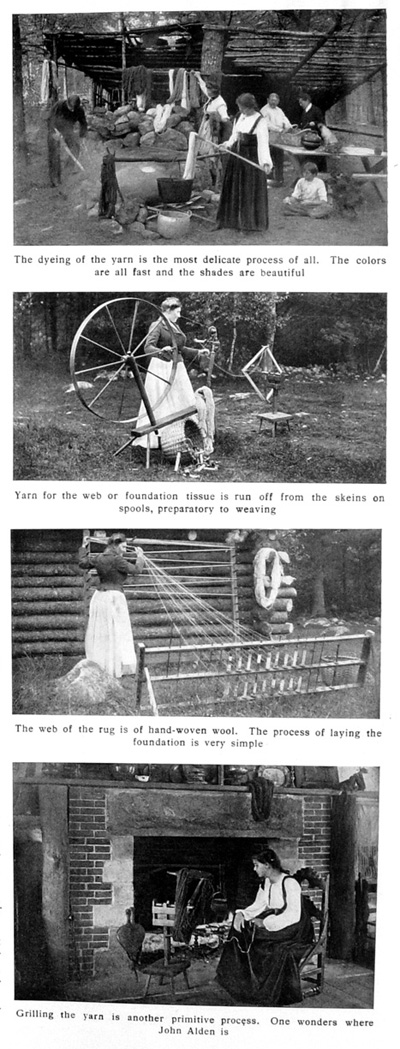

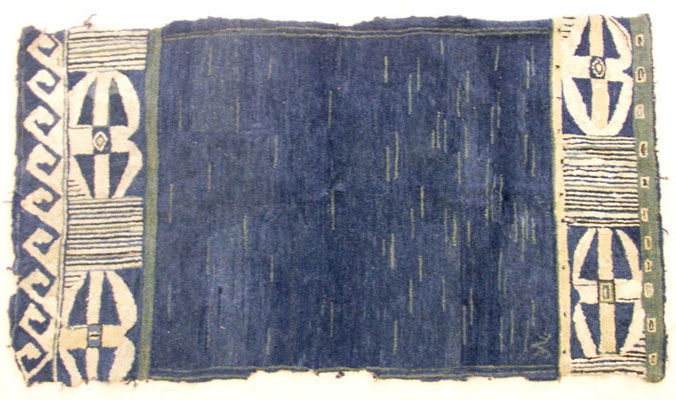

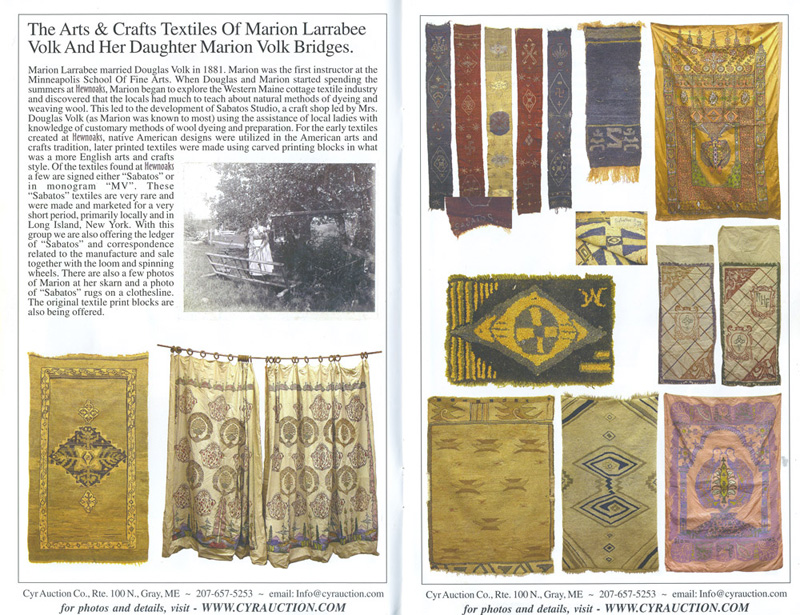

Although the article title is “Douglas Volk and the Arts and Crafts in Maine,” Volk’s wife Marion actually started the first and, according to the author, most important crafts enterprise. The weaving of Sabatos rugs was set up as a communal effort in Center Lovell, where the Volks built Hewnoaks. Their distinctive blue dyes are described in the article, and the development of the Sabatos method from what was basically a hooking technique on burlap to a knotted pile on a handwoven support is duly noted in the text. Rugs with the trademark blue color—including the first Sabatos rug, which Douglas Volk claimed to be the only rug made with a burlap backing (though a small blue mat in the collection of the Maine Historical Society collection also has a burlap support)—were still in the estate when it was auctioned and would have been instructive illustrations. The “first rug” is a miraculous survivor and is now in the Metropolitan Museum of Art. It not only demonstrates the Volks’ use of Native American design but was also illustrated in a 1906 magazine article. It didn’t end up in the 2008 magazine article because it didn’t end up in the author’s inventory.

T

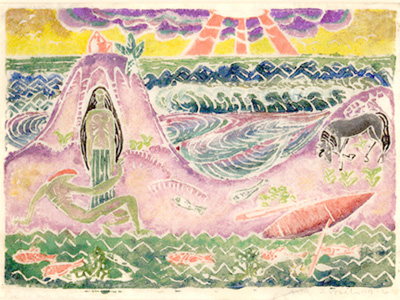

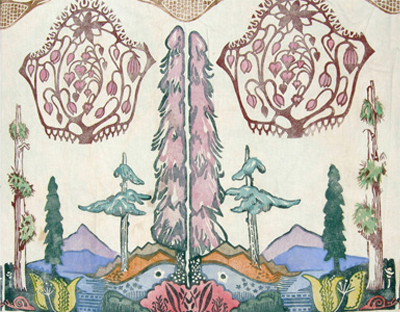

The most egregious omission is mention of the printed textiles, which were much in evidence at the auction and which are a unique and important part of “Arts and Crafts in Maine.” These textiles demonstrate that Hewnoaks was not isolated in an aesthetic bubble as were other Arts and Crafts communities like Roycroft and Rose Valley. The linoleum block-printed textiles were a communal effort as the rug making had been, but unlike the rug designs, which looked backward, the printed textiles advanced a modern style that flourished in Maine during the first decades of the twentieth century.

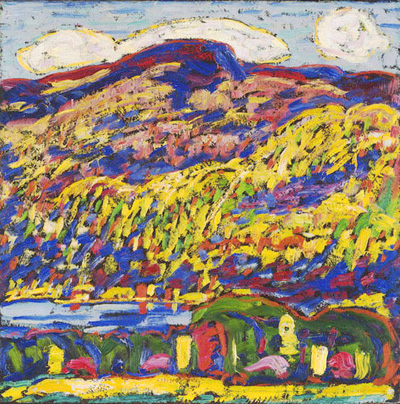

If by “paid little attention” she means that paintings made by a mature artist with an established style and reputation do not show the influence of a 26-year-old painter some two decades younger than he, I bow to her powers of observation. However, if one takes the printed fabrics into consideration, it is easy to imagine how 19-year-old Wendell was benefiting in the shack with Hartley while Daddy Douglas wasn’t paying attention. A pair of curtains printed during the years the author implies Wendell’s wife Jessie just “did metalwork and took to painting the ceilings and rafters of the cottages (see Fig. 10)” shows the lyrical palette and contrived naïveté of Maine’s fauve painters including Hartley, but more particularly Marguerite and William Zorach, Carl Sprinchorn, and Charles Hovey Pepper. The author chose not to use her married name, so if you do “see Fig. 10”, you might not discover that the panels Jessie “took to painting” ended up in the author’s inventory while the curtains did not.

Marsden Hartley

William Zorach

William Zorach

Hewn Oaks

The willful suppression of known history places the objectivity of the author’s writings before she took to dealing under suspicion. She was one in a gaggle of Winterthur women who in the 1970s claimed the territory of American decorative arts for themselves and who now struggle to hang on to their autocratic regency over generations of younger scholars.

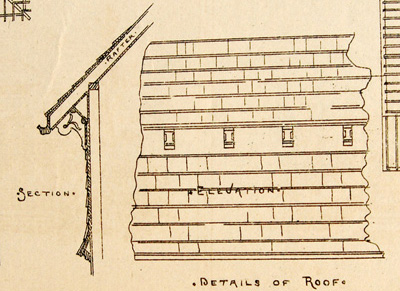

The Builder & Woodworker 1882

Very precise definitions of “rafter,” “roof,” “purlin,” “eave,” “bracket,” and “beam” would be required to deconstruct one of the stacking games designed by Frank Furness, but whether or not one would uncover an “extended rafter tail” pretty much depends on what one’s definition of “is” is.

The Internet is often reviled for its similarity to old-fashioned vanity presses, but it does provide a forum for challenges that advertising-revenue–driven editors of traditional magazines cannot or will not risk. Print media may be good enough to expound ideas, but it is a ponderous, slow method of expanding ideas, something the Internet does with ease. My last Internet posting included a screed about a lecture called “Correcting the Record: The American Arts and Crafts Traveled West to East, Not Vice Versa.” When the lecturer showed a van Gogh ink drawing of a thatched cottage, I thought I had found a clever way to make a transition away from my many points of disagreement with her theory. I referred to notes I had taken earlier during another, more enjoyable, lecture in which I thought I heard a questionable proposition:

“Bruce Smith said Japan was the source of the Greenes’ use of exposed rafter tails, but, he said, the brothers were the first to extend rafter tails beyond the roofline. Au contraire, there in southern France were revealed rustic rafters sticking way out beyond the thatch!”

Mr. Smith recently took the time to correct my faulty observation:

“Actually, my point was that there was no precedent for extended rafter tails (though it is often presumed that Japan was the source). The picture you have in your “chatter” is of purlins. Extended purlins, yes, can be found in France, Japan, Switzerland, Russia, and elsewhere—but not rafters. I tried to distinguish very quickly in my talk (too quickly I now see) the difference between purlins (running out the gabled end of the roof, upon which rafters rest) and rafters (running down the slope of the roof, ending at the eave).”

I am grateful for the correction and am now racking my brain to think of precedential extended rafter tails. Still, I always thought purlins rest upon rafters, not vice versa.